Australia is unique in its approach to asylum seekers. No other country mandates the closed and indefinite detention of children of unlawful, non-citizens. Children may also remain in indefinite detention if a parent has an adverse security finding made against them. This occurs despite Australia’s international human rights obligations. Globally, political and social unrest have highlighted issues that create an intersection between international and national law, human rights, mental health, women’s and children’s health. This article series aims to consider the interdisciplinary factors of children and mothers in immigration detention in coming to Australia. In spite of this focus on Australia, there are important implications for global health.

International obligations and the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child

Australia is party to the United Nations (U.N.) Convention on the Rights of a Child. The Convention provides minimum obligations to comply with duty of care to children in detention[1]. This can be coupled with conventions – the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights, the Charter of the U.N., and the Geneva Declaration of the Rights of Child (1924). These treaties recognise that special care, freedoms, rights, and standards of care are necessary for the appropriate development of a child[2].

Australian migration law and mandatory detention

International obligations despite their number, are not legally binding on Australia. Signed treaties therefore do not oblige Australia to act on the terms in any way. However the federal Migration Act 1958 contains a provision for the detention of children. Section 4AA provides that ‘A minor shall only be detained as a measure of last resort’. It is highly contested that holding children for prolonged periods in remote detention centres does not deter people smugglers or asylum seekers. In fact, there is no evidence for these ongoing practices. In fact the evidence for deleterious effects is chilling.

Effects of mandatory detention on children, mothers and babies

The Australian Human Rights Commission, an independent statutory body held an inquiry into the welfare children in immigration detention. The Inquiry reported serious health and wellbeing issues of those in detention. Findings ranged from high rates of mental illnesses[3], physical ailments[4] including infections[5] and close proximity to adults with mental illness[6].

Mothers and Babies

The health and wellbeing of mothers has a large and immediate effect on that of their children. This is seen most directly in the attachment issues and disorders[7] experienced by mothers and their babies and toddlers respectively. The Inquiry reported ‘parenting under acute material or psychological stress or impaired mental health’ negatively impacted the well being of young children[8]. Parents with mental illnesses or experience severe distress had more difficulty to see and provide for the child’s emotional and physical needs. This had a highly negative impact on the child’s social, emotional, cognitive and language development. Anecdotal reports of a regular visitor to the Melbourne Detention Centre from the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre in Melbourne confounded these findings reporting on the destructive effect mental illness has on families in detention[9], cases of self harm[10] in mothers were also reported.

Child Development

The Report provides that at the time of investigation, at least 12 children born in detention were stateless (not recognised as a citizen of any country), and may be denied rights to nationality and protection. The Christmas Island Detention Centre had asylum seekers housed in shipping containers deemed grossly inadequate[11], with no access to education for over 12 months[12].

Pregnancies

Although there was limited information on pregnancies due to absence of data, some submissions stated that women terminated their pregnancy rather than endure conditions. They reported fear of their babies dying due to conditions and for many leaving the detention centre at 34 weeks for delivery meant separation from partners.

Mental health disorders

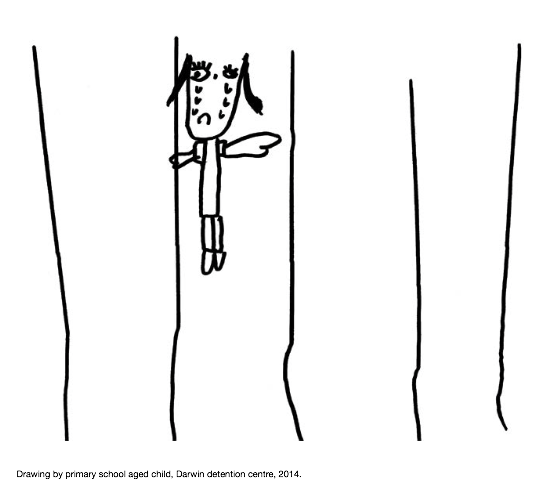

Between 1 January 2013 and 10 July 2014, the rate of mental health diagnoses was approximately 14 per cent amongst new mothers in detention. The inquiry found high reports of self-harming mothers, and mothers under suicide watch, as at July 2014[13]. The experience and high frequency of mental health difficulties experienced by asylum seeker mothers and their children are expressed in a number of findings. Eighty-five per cent of children and parents have indicated that emotional and mental health has been affected since being in detention[14]. With no positive responses, only 1 – 2 per cent of children said they feel sad none of the time (Chart 23, Chart 52)[15]. With no positive responses to detention, the Inquiry found that the most common reports were of sadness and ‘constant crying’[16]. Worry, restlessness, anxiety and difficulties eating and sleeping were also highly reported.

Latest developments

The Australian Government recently passed the Australian Border Force Act. The new legislation effective from 1 July 2015 makes it an offence for an “entrusted” person (defined widely enough to include contracted and consulting employees such as doctors and nurses) to record or disclose “protected information” they obtain, providing a penalty of 2 years imprisonment. This legislation has been disparaged as an attempt to discourage the disclosure of human rights violations and child abuse inside Australia’s detention centres.

Practitioners voiced their deep concerns and firm stance against the secrecy laws in an Open Letter to the prime minister as a direct violation of pre-existing legal obligations to report child abuse. The introduction of the new law has been considered a reactionary response to recent events, involving allegations of sexual abuse against women and children, and would have severe, resounding consequences for those who spoke out. The Inquiry has brought great attention to asylum seekers in Australia as a highly vulnerable population. In a holding pattern of poor health and well being with little idea of future prospects, action from all disciplines concerned for health and human rights is paramount.

[1] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Conventions on the Right of the Child, art 37(b).

[2] Ibid, part 1.

[3] Commonwealth, Australian Human Rights Commission, The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry in Immigration Detention (2014), 65-7.

[4] Ibid 121-22.

[5] Ibid 97-8.

[6] Ibid 121–2.

[7] Ibid 65-7.

[8] Ibid 87-9.

[9] Ibid 87-8.

[10] Ibid 92[4].

[11] Ibid 76[8].

[12] Ibid 146-7.

[13] Ibid 99.

[14] Ibid 58.

[15] Ibid 88, 154.

[16] Ibid 58.